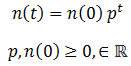

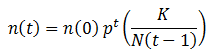

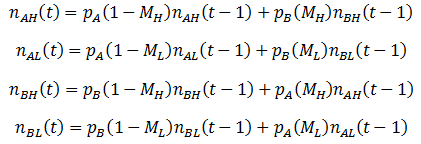

Model of a binary system

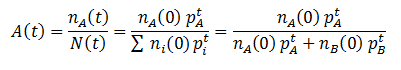

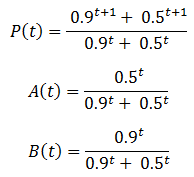

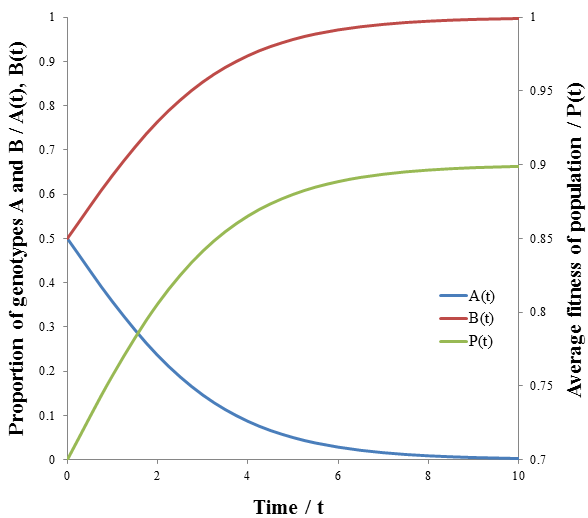

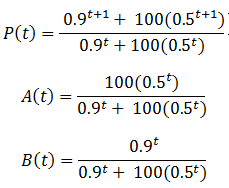

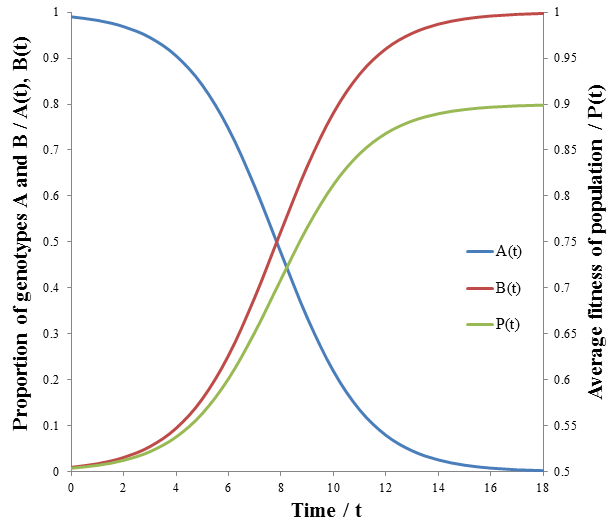

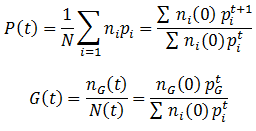

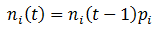

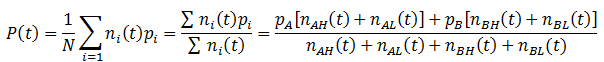

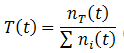

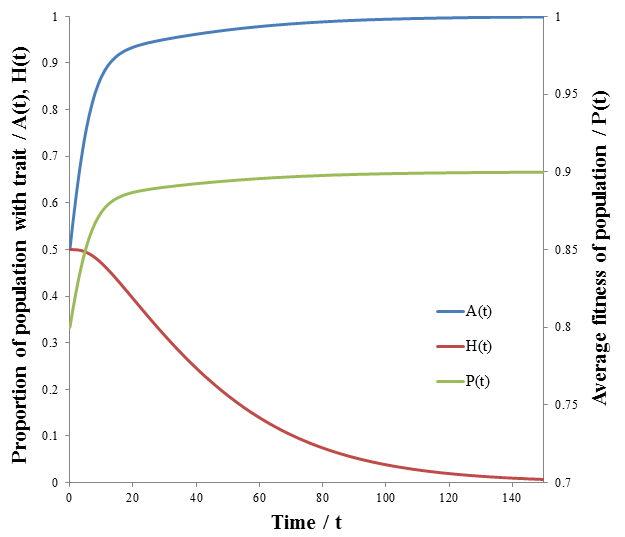

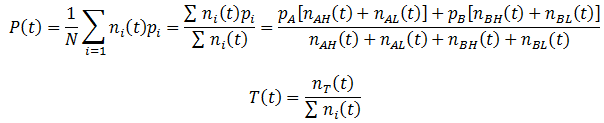

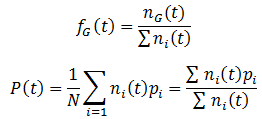

We can follow the relative amount of each phenotype simply by computing the ratio of the number of organisms with that phenotype to the total size of the population. For instance, the relative amount (A) of phenotype A is given by:

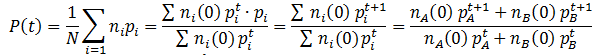

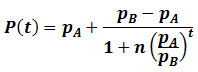

Similarly, we can monitor the average fitness of the population as a function of time by taking a weighted average of the fitness levels present in the population:

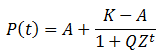

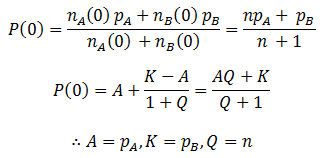

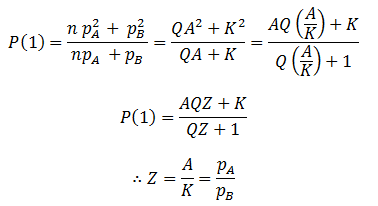

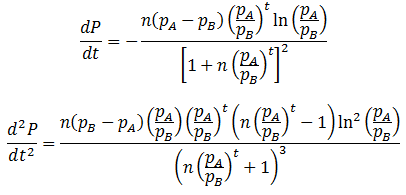

In its present form however, differentiation of P(t) gives a complicated function which is difficult to analyze. The sigmoidal shape is consistent with a logistic curve, whose form is simpler and more feasible to differentiate. Thus I attempted to find an equivalent form of P(t) in terms of the generalized logistic equation:

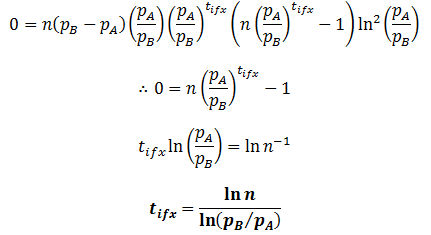

Also, the inflexion point does not exist when pB=pA. This is expected, as then there is really only one group and thus the average fitness would be constant. Inflexion only occurs at positive time when pB>pA and n>1, or n<1 and pA>pB. In other words, when there are initially more unfit organisms than fit organisms.

Lastly, this equation elucidates the specific relationship between the relative fitness of two phenotypes and the rate at which their frequencies in the population change. The tifx values can be taken as a measure of how quickly the population changes, a smaller value indicating a faster rate of change. Therefore, the rate increases with the logarithm of the phenotypes’ relative difference in fitness.

Generalizing the binary model

A model for single mutations

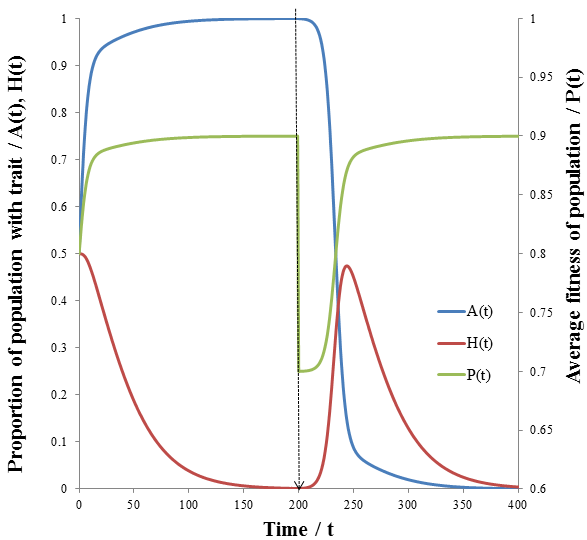

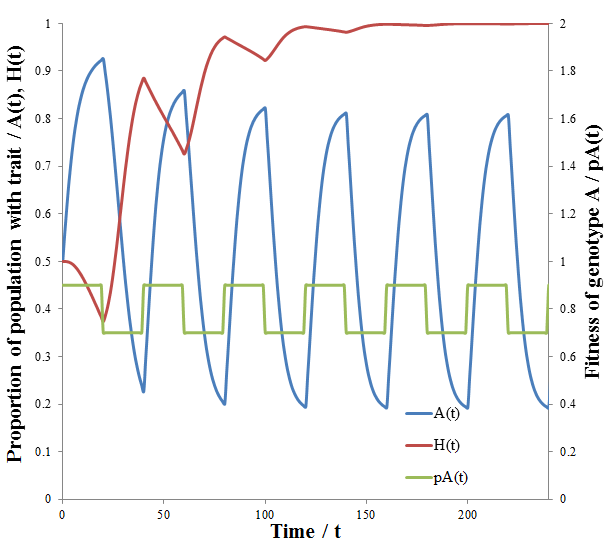

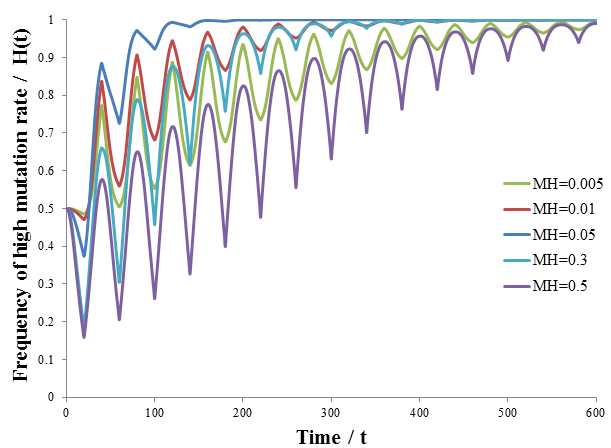

Mutation rate as a mutable trait

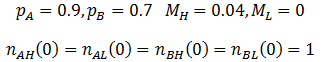

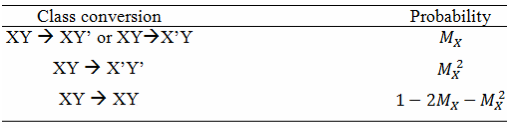

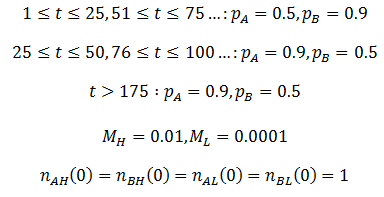

We still have four possible organism classes (AH, AL, BH, and BL). Mutation of the A/B phenotype and the mutation rate are independent. Now I define M as the absolute probability of single mutation of either of these traits. The resulting probabilities of all possible conversions are shown in the following table. I use XY to represent the organism class: X refers to H/L and Y represents A/B. Primes indicate a change in the indicated trait.

Genotype and sexual reproduction

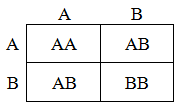

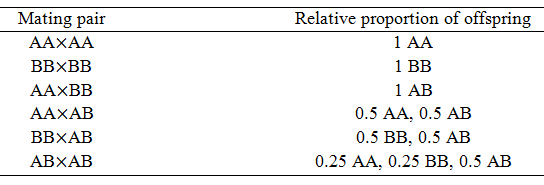

The inheritance of the alleles from each parent are independent, thus it is easy to calculate the proportion of each genotype expected for in the offspring. This is traditionally shown as a Punnett square. For instance, for the mating of ABxAB:

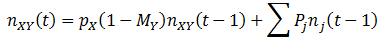

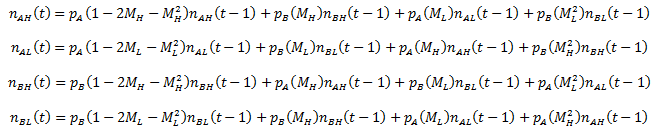

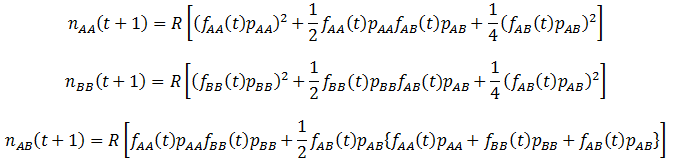

The fitness (p) of the organism class’s phenotype determines the proportion of them that reproduce successfully over a time increment (parental organisms are assumed to die after each time increment, leaving only offspring). The calculation of the amount of each genotype that are produced is complicated by how at any given time there may be different frequencies of organisms with each genotype in the population. I assume that mate selection is random (organisms do not show preference for mating partners based on genotype/phenotype). Thus, the probability of each of the above mating pairs are proportional to both the fitness values of each genotype and their frequencies (f) in the population. The number (n) of each genotype offspring produced can be found by summing the numbers produced by all possible crosses listed above. This is done over discrete time intervals as with the mutation models:

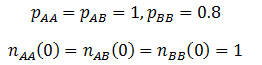

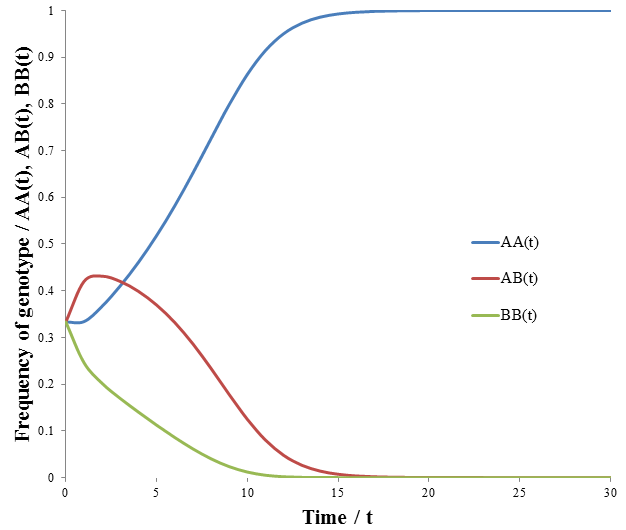

Similar frequency profiles are obtained in the case where the A allele is recessive, but still the most fit. However, it is interesting to compare the rate at which the AA genotype out-competes the others. I simulated the recessive case using the following parameters:

Heterozygous advantage

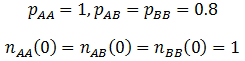

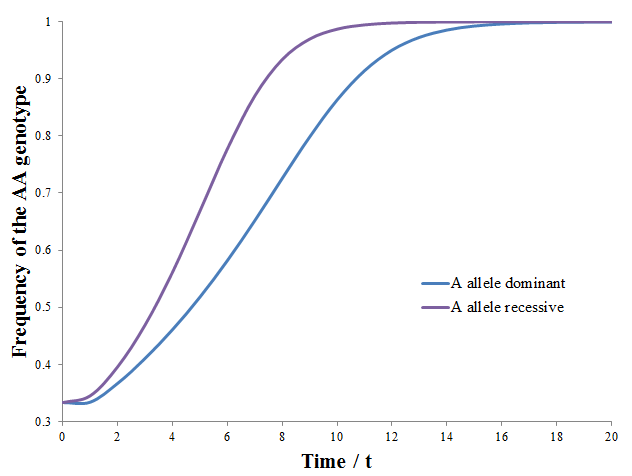

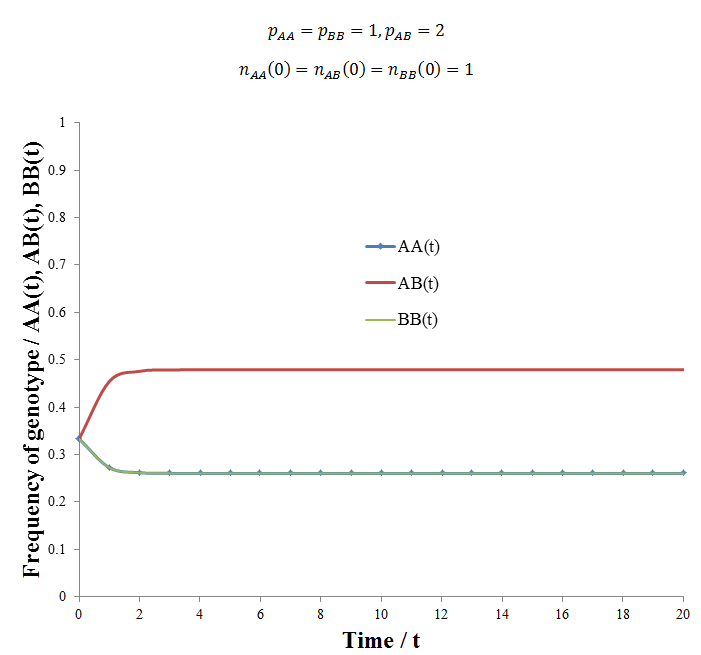

An interesting question results from this: what is the ideal proportion of each genotype in such a population, how is this affected by the relative fitness of each? It is tempting at first glance to think that since the heterozygous genotype is most fit the equilibrium ratio will favour a maximum amount of AB, 50%. However, my analysis shows the situation to be more complex than this, a supporting example follows. The figure below gives the frequencies of each genotype with respect to time calculated using following parameters:

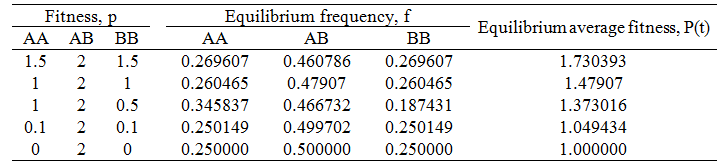

In order to test the validity of my explanation above for the 0.26047/0.47907/0.26047 AA:AB:BB ratio, I did the simulations again for different fitness values of each genotype. The results follow in the table below.

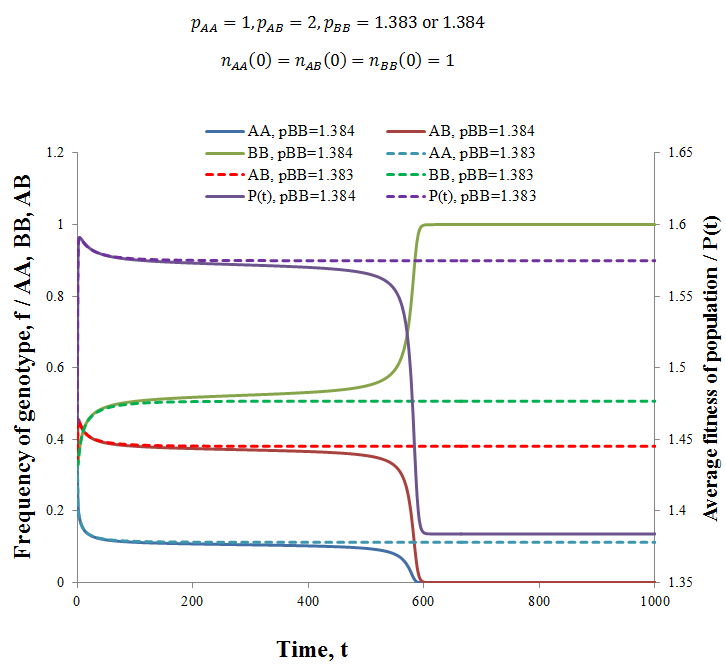

Interestingly, upon trying a variety of fitness values I found that the heterozygous genotype having greatest fitness did not guarantee that the population would contain a mix of genotypes at equilibrium. Instead for any set of fitness values where pAB > pAA, pBB there exists many combinations of pAA and pBB values such that the heterozygotes are out-competed by one of the homozygous genotypes. That is, the condition pAB > pAA, pBB is necessary, but not sufficient for a heterozygous-containing equilibrium to result. Observe below, where I used the parameters:

I included the average fitness in this figure because, interestingly, it actually decreases with time initially. This is the first case in this entire investigation where we have seen average fitness decreasing with time. This may seem to contradict what I presented as the basis of evolution, that differential selection of more fit organisms gives rise to increasing fitness in the population over time. However, this is really just a result of the starting conditions chosen and the properties of co-dominant genes. If the population starts at a position far from equilibrium, but more fit than at equilibrium, its fitness must decrease until equilibrium is reached. For instance, in a more extreme case imagine starting with only heterozygous (AB) organisms. At most, they can sexually reproduce to give offspring that are 50% AB, thus the amount of AB would have to decrease even if the AB genotype confers greatest fitness. Therefore there is a distinction between stability and fitness. We can thus amend the previous statement: populations approach the maximum average fitness that can be attained stably.

Conclusion

--The frequency profiles of two competing traits in a population follow a logistic curve in a stable environment.

--The rate at which the frequency of heritable traits in a population change is greatest when the frequencies of the competing traits are equal.

--The time required for one trait to out-compete another varies with the logarithm of the traits’ relative fitness values.

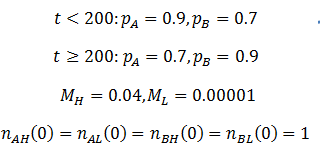

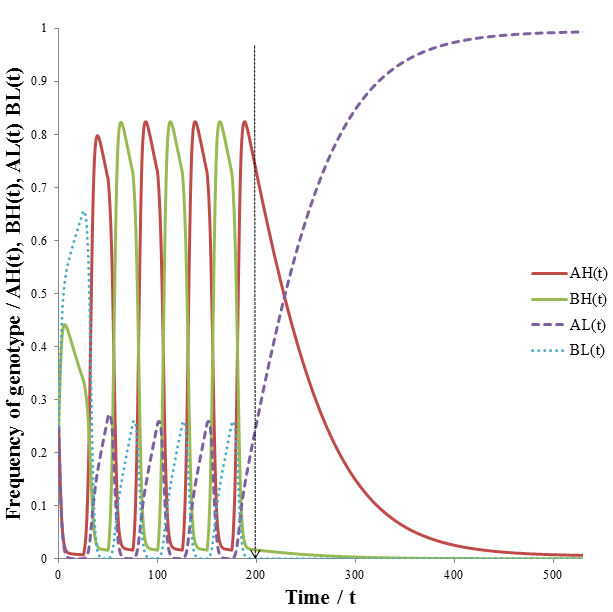

--Mutation is advantageous and thus selected for during times of environmental change, but is detrimental when the environment is stable.

--For any population there exists an optimum mutation rate based on the frequency and size of environmental changes.

--Having a mutable mutation rate is beneficial when the variability of the environment changes.

--In addition to the direct fitness conferred to an organism by a particular trait, the resulting fitness of its offspring must also be considered when appraising its overall competitiveness.

--The selection of a fit recessive allele occurs faster than for a dominant allele.

--If a homozygous genotype is more fit than the other genotypes, it will dominant the population at equilibrium.

--Heterozygous advantage can result in an equilibrium mixture of each genotype, where the ratio depends on the relative fitness values of the genotypes. However, the heterozygote having highest fitness alone does not guarantee that such equilibrium will occur; there is also dependence on the homozygotes’ fitness values.

Mathematical modelling can be a useful check of our assumptions and reasoning, to verify they made the predictions that we think they do. It is reassuring that my models, although relatively simplistic, corroborated many predictions of evolutionary theory and population dynamics.

I argued at the start of this article that modelling could also be used to address questions that are not testable experimentally. A good demonstration of this is my study of heterozygous advantage. This phenomena, the heterozygous state having greater fitness than either allele alone, is sometimes used to help account for genetic variation in populations. Indeed, my simulation results predicted that heterozygous advantage could maintain genetic variation by allowing a mixture of genotypes at equilibrium. However, I was also able to show that heterozygous advantage alone did not always produce such a mixture. Though this result was very feasible to show mathematically, it would be challenging to demonstrate experimentally. Unlike with real organisms, when running a simulation you have full knowledge and control of the fitness values assigned to each genotype.

The simplicity of the models I have presented was convenient when performing the calculations; I could do them using Microsoft Excel. However, it limited the types of questions that I could study. For instance, I assumed the population was infinite to simplify the model. There are many evolutionarily important consequences of smaller population sizes though, such as genetic drift. Furthermore, I studied cases where there are only a few discrete phenotypes in the population. In contrast, for real populations many phenotypes are quantitative, they vary over a continuous spectrum. It would be interesting to study the dynamics of a population with several quantitative traits. In this case, fitness would be a complex function of all traits possessed by the organism, as well as the state of the environment. This raises an intriguing issue that I have not been able to examine through my current models: local versus global maxima of evolutionary fitness. We can imagine a fitness landscape, a surface that visually relates the fitness of an organism to all of its traits and the current environment. Mutation and genetic recombination from sexual reproduction allow a population’s members to transverse the fitness landscape, moving towards a fitness maximum. However, depends on the shape of the landscape, this may not be the global maximum. In a future article, I will study how evolving populations move through fitness landscapes. The problem of local minima is of particular interest to me, including what conditions and through what mechanisms populations are able to find the global maximum. The problem of finding global maxima has applications to a variety of fields, not just evolutionary biology. Indeed, algorithms inspired by evolution are often used to search for solutions to optimization problems. Elucidating how the problem can be solved in the case of evolution may provide new insights and strategies to solving it in the general case. Unfortunately, the complexity of the model needed for this a simulation is beyond what is reasonable to do in Excel. It is possible to design a computer program to do the calculations though, the develop of such a model may be the topic of a future article.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed